From weSTEM

Intersectionality 101: What the Numbers Don’t Tell us about the Experiences of Women in STEM

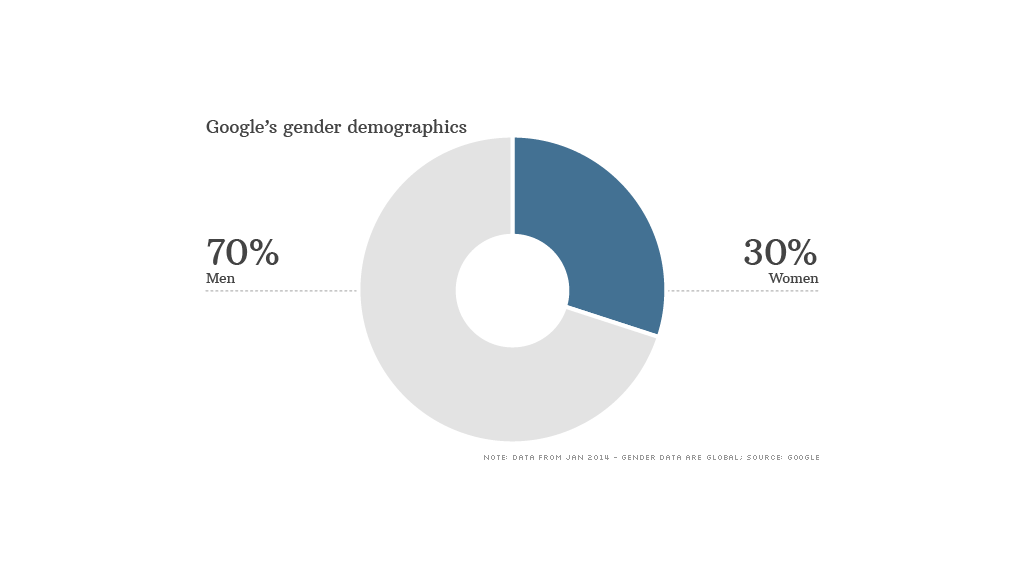

Because women have been historically marginalized in STEM fields (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), it became essential to collect data about their representation. However, it is equally important to understand what such data may not tell us. Consider the following diversity report graph from one of the tech industry giants, Google:

The above graph reported by CNN shows the percentage of women compared to the percentage of men working at Google. Not only is the graph rooted in the gender binary, but it also reduces men and women into monolithic blocks on the basis of gender. However, gender is only one of the many intertwined identities women may hold. Graphs such as the ones above may be illusive. It is possible, for example, that women of color do not make up even a single percentage of the pie chart. Hence, graphs such as the one above are insufficient for understanding diversity.

An increasing number of scholars acknowledge how people’s experiences are molded by the multitude of their identities and have come to adopt the intersectionality framework. Intersectionality, defined by Kimberle Crenshaw in 1991, is a lens through which one can consider the complexity of human identities and experiences. Intersectionality is used to analyze the co-construction and connections of different aspects of identity, such as gender, race, sexuality, and class, among others. For example, an Arab Muslim woman who works in an engineering company does not experience her job separately as Arab, Muslim, or a woman but rather as the interaction of all three identities. There may not be a proper space allocated for her to pray comfortably and she may be forced to regularly debunk orientalist myths about her country of origin and answer questions about her attire choices on daily bases and feel unwelcomed in “boy’s clubs” developed for career networking.

This example shows how one-dimensional quantitative analyses fail to grasp the scope and complexity needed for genuine advance in diversity. The intersectionality approach, on the other hand, demands statistics beyond the single dimension and allows us to imagine real women with complex intertwined identities. Hence, intersectionality shifts the focus of diversity debates away from the gender binary and toward complex challenges women navigate in STEM and elsewhere. So when we take a moment to consider the ratio of male to female students in a STEM classroom, note that it is not enough. Adopting an intersectional mindset in an academic or professional setting by analyzing individuals and hearing their stories to view their complex identities in all their many facets of reality is crucial for moving forward in making STEM genuinely diverse and inclusive.